I have asked our publisher Lisa Milton to read this letter to you at your memorial. This is partly cowardice. At your request, I read your tribute to John at his funeral. I wanted to do that for you and for him, but there was a tough trade-off, leaving Andy’s hospital bedside, missing one of the last days of his life. Of course I choked, and I don’t want to do that today.

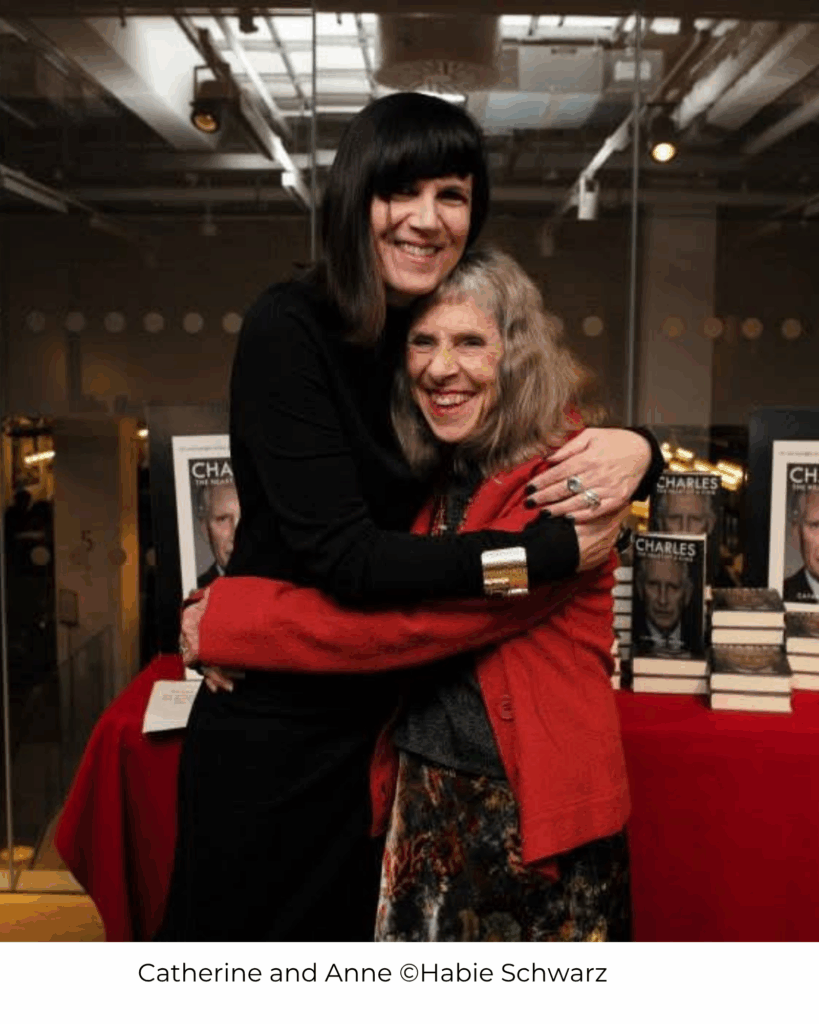

But I have a much happier reason for asking Lisa to do this. Both she and I want to celebrate the closing phase of your life, when you became, to use your term, a “published author”.

Our joint memoir, Good Grief, would never have happened without the power of your writing. Those letters you wrote to John are the backbone of the book and, as Cassie recently pointed out to me, material future historians will find riveting, documenting the day-to-day experience of living through the pandemic and rebuilding a shattered life, even as politicians and the media told you that people your age didn’t matter, that you were expendable.

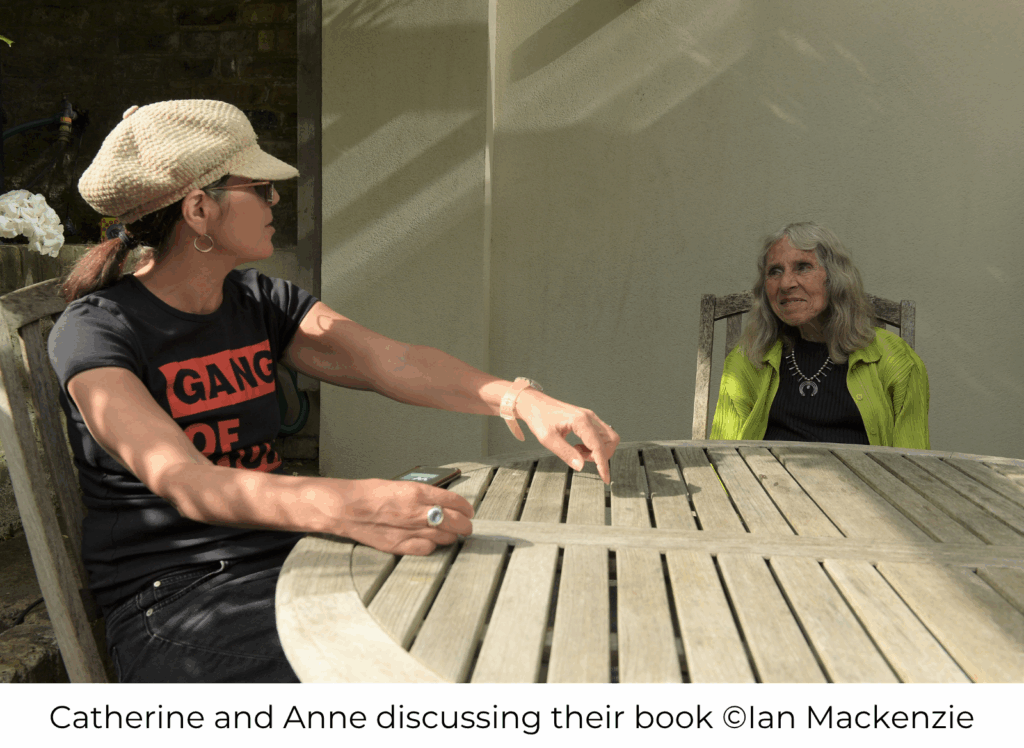

Nobody is expendable but you leave such a huge gap in so many lives. I feel it every day. We were planning our next book for Lisa, and also you wanted to turn our joint experience to helping others through bereavement. You had ideas about hosting advice sessions, writing pamphlets, doing joint interviews. You thoroughly enjoyed giving interviews. For me the process was a white-knuckle ride because you had no filter, yet it was all the more exhilarating for that. So many times interviewers thought we were crying when it was laughter we were suppressing.

Dearest Anne/Mummy, dearest twin widow, dearest Mommy, dearest Published Author, your appetite to write more, do more, be more, seize life never diminished. What better way for us to celebrate you than to follow your blazing, hilarious, high-watt lead?